By Vanessa Formato

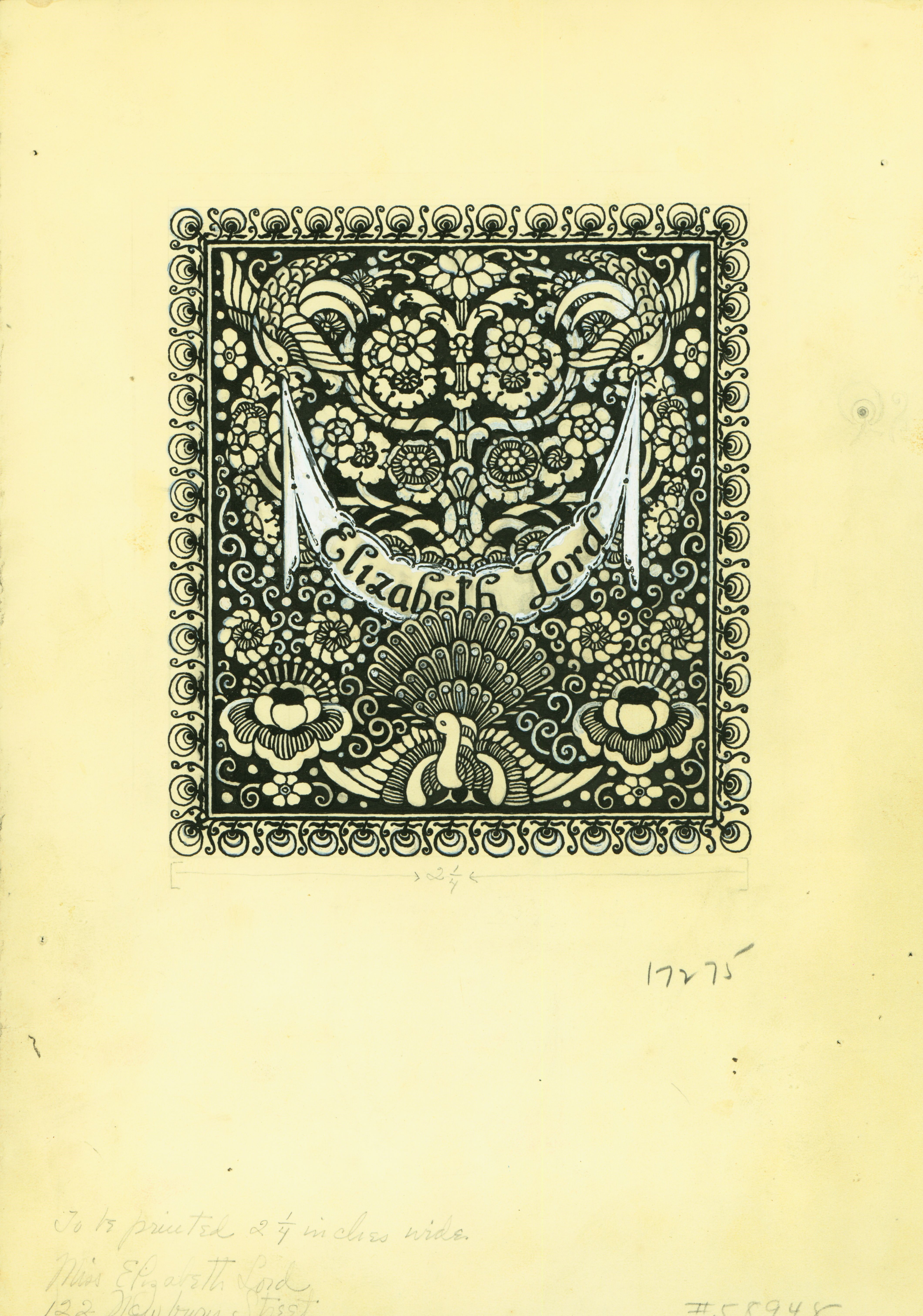

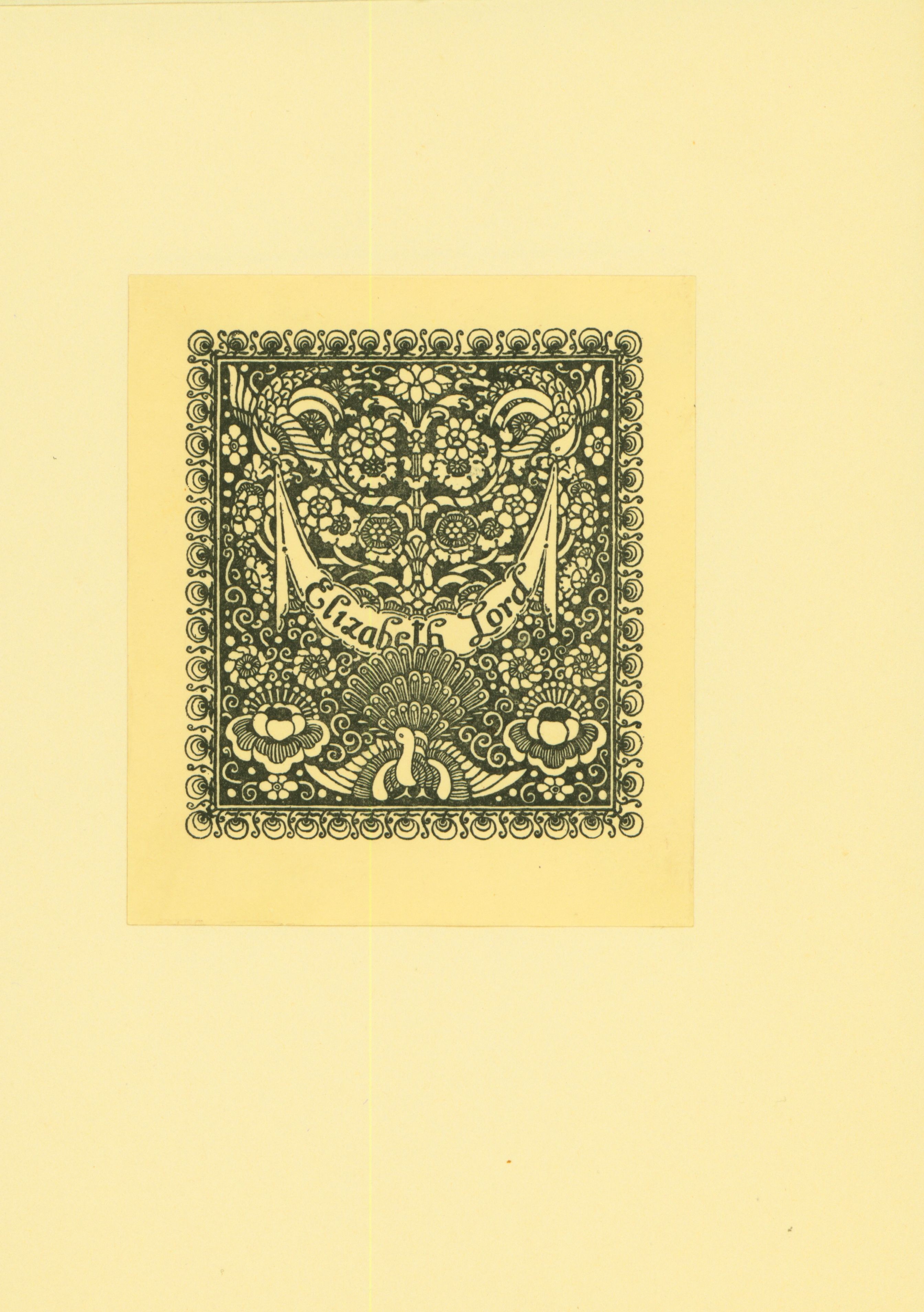

Elizabeth Lord was a student of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in the early 1920s, when the bookplate craze was at a fever pitch. Recently transferred with the School of the Museum of Fine Arts Records to Tufts Digital Collections and Archives, Lord’s bookplates are excellent examples of the beauty and whimsy of this lost art.

Bookplates—also sometimes referred to as ex libris, Latin for “from the library of”—are nearly as old as the printing press, with the earliest known examples dating back to Germany in the mid-1450s.[1] On the most basic level, bookplates are pieces of art pasted into a book to denote its ownership, but, of course, they’re really more than that. At the dawn of mechanical printing, book ownership was still primarily a rich man’s game, and having one’s own bookplate designed and produced was a further declaration of status. Many early bookplates were strongly tied to their owners’ heritage and commonly featured coats of arms.[2]

The 19th century marked both the rise of the middle-class[3] and a shift from copperplate to more affordable wood engraving techniques among makers of bookplates.[4] Bookplates surged in popularity both as collectors’ items and works that could be commissioned for one’s own personal library. As collecting became a popular pastime, classification systems emerged to help enthusiasts identify historical examples. Early armorial bookplates (around 1500-1800) generally fall into one of four categories: early English (coats of arms and shields), Jacobean (ornate, often referencing family crests), Chippendale (lighter and highly decorative), or Ribbon & Wreath (“spade-shaped shields” and ribbon and wreath motifs).[5]

In the United States, though, the newly wealthy had no tradition of coats of arms to fall back on to design their bookplates. Instead, they requested imagery related to the things they loved the most: hobbies, loved ones, scenes of home. According to Lew Jaffe, a longtime bookplate collector, this unique sensibility spurred the explosion in creative bookplate design that characterizes American bookplates between the 1890s and 1920s.[6]

Many American bookplates during Elizabeth Lord’s time are characterized broadly as pictorial in style, drawing on a wide range of artistic influences to depict a practically endless array of subjects. More specifically, trends in bookplates during this era track with the big Western artistic movements, including art nouveau, art deco, cubism, neoclassicism, modernism, and Arts and Crafts.[7]

While both World Wars and the creation of universal bookplates—boxes of decorated, fill-in-the-blank sheets that were affordable to all—would damage the popularity of the hand-crafted bookplate, the 1920s and 1930s represent a unique and innovative high point for the art. Many of the advancements being made in the worlds of graphic design and typography in this moment would translate perfectly to the bookplate.[8]

One striking example from Lord’s portfolio that shows off the sensibilities of the day is a bookplate made for Imogene Hogle Putnam, who in 1924 was a faculty member at Emerson College in Pantomime and Community Drama.[9] Seen here, Hogle’s bookplate features ornate pattern work, hand-drawn lettering, and theater-related imagery.

Lord from an Annie Putnam, found together with Imogene’s bookplate.

In a bookplate designed for Donald and Stella Williams, four people uncover buried treasure in the sand, surrounded by leafy flourishes and classical busts. Looking closely, one can see the original pencil sketch beneath some of the ink work. In the blank space around the plate, Lord has blocked out her drawing and practiced some of her lettering, perhaps before committing it to the plate itself.

The records of Lord’s time at the SMFA suggest she was an accomplished student and well-recognized for her talents. According to annual reports, Lord was appointed a Student Assistant in the Department of Design in 1921 as the school scrambled to prepare for 1922’s larger-than-average incoming class (324 enrollees, excluding “special” and lecture-only students, versus 1921’s 254).[10] In a 1922 annual report, Lord is praised for winning an honorable mention in a local bookplate contest for the Seamen of the American Merchant Marine.[11] By 1924, she had achieved an instructor-level position at the school as an Assistant in Design.[12]

For more information about this collection, please see our previous announcement or the finding aid for the School of the Museum of Fine Arts Records. For more information on accessing this collection, please contact Tufts Digital Collections and Archives.

[1] Keenan, J. P. (2003). The Art of the Bookplate. New York: Barnes & Noble.

[2] Princeton Architectural Press. (2019, September 24). A Brief History of Personalized Bookplates. Retrieved from https://lithub.com/a-brief-history-of-personalized-bookplates/

[3] Princeton Architectural Press. (2019, September 24). A Brief History of Personalized Bookplates. Retrieved from https://lithub.com/a-brief-history-of-personalized-bookplates/

[4] Keenan, J. P. (2003). The Art of the Bookplate. New York: Barnes & Noble.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Oatman-Stanford, H. (n.d.). When Book Lovers Guarded Their Prized Possessions With Tiny Artworks. Retrieved from https://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/when-book-lovers-guarded-their-prized-possessions-with-tiny-artworks/

[7] Keenan, J. P. (2003). The Art of the Bookplate. New York: Barnes & Noble.

[8] Keenan, J. P. (2003). The Art of the Bookplate. New York: Barnes & Noble.

[9] https://archive.org/details/emersonianemerso1924unse/page/n11/mode/2up

[10] https://archive.org/details/annualreportofmu1921muse/page/n127/mode/2up

[11] https://archive.org/details/annualreportofmu1921muse/page/124/mode/2up

[12] Pierce, W. (1930). History of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 1876-1930. Boston, MA: Museum of Fine Arts.